Evan Zimmerman

In 1966-67, the primary season in its Lincoln Heart home, the Metropolitan Opera supplied its first-ever manufacturing of Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten. Designed to point out off the brand new home’s a number of, hydraulic levels, Robert O’Hearn’s set moved up and down between the imperial gardens on excessive and the proletarian underworld beneath. The identical capability impresses nonetheless.

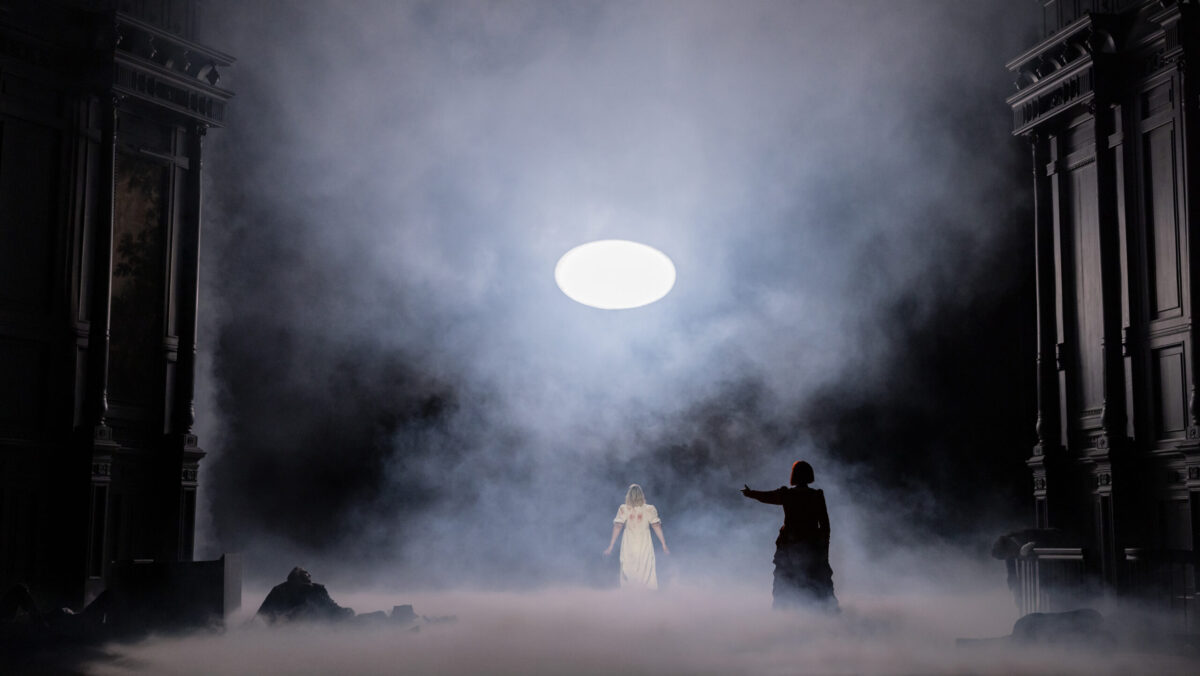

Within the Met’s new Salome, directed by Claus Guth and designed by Etienne Pluss, Herod’s palace is a cavernous black field with Victorian ornaments that rises portentously to disclose an equally grandiose obvious cellar area beneath it, the makeshift jail through which John the Baptist (Jochanaan) is chained to a rear nook. When the captain of the guard (on this manufacturing the top butler) agrees to Salome’s demand to talk with the prisoner, they each descend into the cellar to the music that normally accompanies Jochanaan’s emergence from his cistern.

As Salome descended the treacherous triple-angled stairway, adopted by the morbidly curious captain/butler Narraboth, a type of déjà-vu occurred to me. Wasn’t this scene surprisingly paying homage to Act II of Fidelio, of Leonore’s descent into Florestan’s jail dungeon adopted by the jailkeeper Rocco—who, like Narraboth, can be following orders?

Karen Almond

“Es muss schrecklich sein, in so einer schwarzen Höhle zu leben” (it should be horrible to stay in such a black cave), wonders Salome; “wie kalt ist es in diesen unterirdischen Gewölben”(how chilly it’s in these underground caverns), feedback Leonore. Who ever thought to search out any similarity between Fidelio and Salome? No such intention is more likely to have impressed both Guth’s manufacturing or Pluss‘s set. However, the juxtaposition yields some dividends.

Precisely a century separates the primary model of Beethoven’s Fidelio (referred to as Leonore, 1805) from Strauss’s Salome (1905). The Fidelio story originated in a late 19th-century play based mostly on a real story; the Salome story has sources within the New Testomony (Mark and Matthew) and within the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus. Every includes an unjustly incarcerated political prisoner who cries out with appreciable dignity.

The distinction is of their vital others. One in every of them is rescued by his heroic spouse. The opposite is murdered on the will of a vengeful teenager. The primary carries the transformative optimism of a revolutionary age; the second is overwhelmed by the oppressive environment of declining empire– whether or not that of the Romans or the Victorians or the Habsburgs. I’ll depart it to historians of antiquity and Bible students to touch upon the supply depictions of cultural pessimism and perverse sexuality. We name the years across the flip of the 20thcentury the fin-de-siècle as a result of the time and temper counsel the tip of an outdated period greater than the beginning of a brand new one.

Evan Zimmerman

Then again, those self same fin-de-siècle years—say the last decade from Oscar Wilde’s Salome to Richard Strauss’s—have been marked additionally by revolutions in human understanding. These embrace the invention of sexuality, each as a precept of identification and as a scientific discourse. The invention of sexuality included homosexuality as a marker of identification reasonably than a classification of an act. Personally and politically, sexuality now carried a double potential. Liberating when tied to the emancipatory politics of the sense of a brand new period, it may additionally debilitate when saddled with cultural and political despair. Within the first column: first-wave feminism and homosexual rights; within the second: misogyny and the affiliation of femininity with hysteria and perversion. From Wilde to Strauss, Salome lives on this second column.

In her extensively learn 1970 e-book Sexual Politics, Kate Millett argued that Salome’s fixation on John the Baptist’s pores and skin, hair, and mouth in Wilde’s play may very well be understood because the displacement of male (Wilde’s) gay want. Maybe, however the ironic end result of this notion is its repetition of the play’s personal primary misogyny. First rendered right into a determine of perversion, Salome now vanished fully as a girl. In fact, the play additionally accomplishes actually this act of violence in Salome’s execution on Herod’s orders. Within the Biblical account, Salome is claimed to go on to a later life, one together with marriage and youngsters.

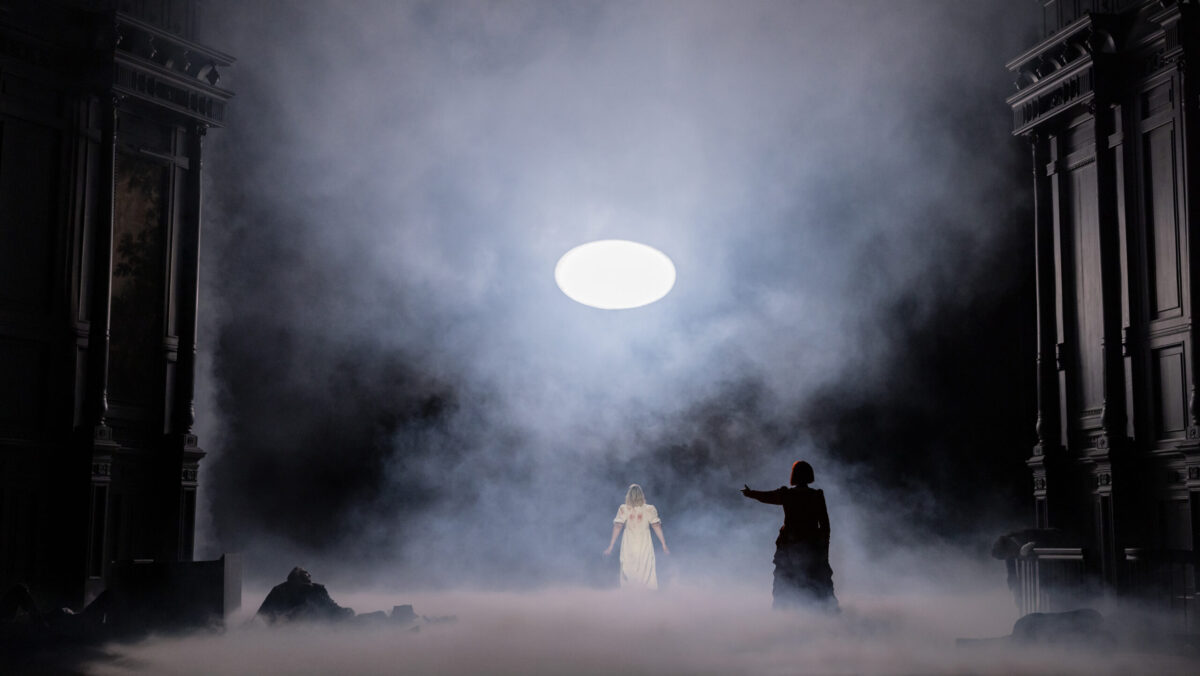

Claus Guth’s Salome is just not executed by Herod’s troopers; she merely retreats upstage. A memory of Patrice Chéreau’s Elektra, who stares into area for the time being of her scripted loss of life? However not like Elektra, who understands all the pieces, Salome understands nothing. Is she escaping the palace? Has she realized one thing about violence and restoration? Her survival could keep away from a misogynistic cliché —that hyperlink between opera extra typically and “the undoing of girls,” in Catherine Clément’s now basic formulation.

Evan Zimmerman

However Guth’s manufacturing carries its personal endemic misogyny. On the one hand, Guth’s Salome is explicitly and convincingly portrayed as a sufferer of childhood sexual abuse, more than likely on the hand of her stepfather Herod. A lot is totally supported by the textual content: “Es ist seltsam, dass der Mann meiner Mutter mich so ansieht” (It’s unusual for my mom’s husband to have a look at me that approach). As opinions have extensively commented, Guth’s manufacturing unfolds by a sequence of pantomimes involving a sequence of doubles embodying levels of Salome’s childhood and adolescence. And as Zachary Woolfe aptly famous in his assessment, Salome’s manipulation of Narraboth includes abusive fondling that may be inferred as a repetition, an appearing out, of her personal historical past of victimization by Herod.

Trauma includes the undoing of the self, and there’s no overestimating its devastation. However that’s not to say that restoration is unimaginable, not less than to a degree of performance. Such was the fundamental premise of Sigmund Freud’s early psychoanalytic principle. Having witnessed innumerable instances of abused younger girls throughout his apprenticeship on the fabled Paris Salpêtrière hospital, Freud developed his preliminary principle of “hysteria” as an sickness ensuing from the trauma of rape. As this primary articulation developed right into a normal principle of the unconscious, Freud deserted what turned recognized euphemistically because the “seduction principle,” changing sexual victimization as the fundamental downside with the repressed want for sexual contact, a shift for which he has been amply criticized.

Evan Zimmerman

For these critics, Freud’s change of place resulted from the denial that sexual abuse may exist in such overwhelming numbers. The repetition or “appearing out” of trauma, whether or not by incapacitating psychosomatic signs or by the serial displacement of the unique violence into the abuse of different victims, makes clear the dearth of restoration. The “working by” of each trauma and its recurrences—for Freud the normative various to “appearing out”—is probably restorative of each performance and ethical company.

These paths are fraught with political points. Although the shortcoming to work by previous trauma can’t be assumed to represent failure—that will quantity to blaming the sufferer—the idea that working by is categorically not potential may also quantity to a misogynistic prejudice. And that’s the place Guth’s manufacturing of Salome falls brief.

For Salome to show merely right into a type of deviant, as her necrophilia appears greater than ever as an instance in Guth’s last scene—appears solely to consign her to the identical world of depravity that consumed her youth. On this respect the manufacturing unintentionally repeats the identical kind of violence towards women and girls that it portrays within the first place. Salome’s last walk-out stays illegible. In equity, maybe any legibility would require a sign from the work itself that’s merely not there.

Evan Zimmerman

The paradigms of decadence and symbolism into which Wilde and Strauss insert their variations of the Salome story contain a retreat into sensual interiorities that depart little room for the skin world of political or ethical functioning. The psychoanalytic paradigm that emerges at the moment pays rigorous consideration to deep realms of want and violence. These change into the topography of the unconscious, which Freud claimed to be the primary to chart scientifically whereas on the similar time crediting poets and different artists with its pre-scientific understanding.

In his scientific follow, Freud strove to alleviate sufferers who have been affected by incapacitating signs, disturbances rising from the unconscious and ensuing from unhealed psychic wounds. “Wound” is the interpretation of the Greek phrase “trauma.” In describing the purpose of such remedy as performance and explicitly not as happiness, Freud hoped to revive these sufferers to a type of citizenship on this planet. In different phrases, to an ethical and political life, at no matter scale.

Beethoven’s Leonore is the epitome of the ethical citizen, understood in late 18th century, Kantian phrases of common ideas and legal guidelines. Her private and political values are equivalent. Her rescue of her husband extends seamlessly to the liberation of scores of political prisoners. Earlier than she acknowledges her husband, she vows to rescue the unknown prisoner within the dungeon, irrespective of who he could also be. Within the mid-20th century this precept of universality turned referred to as human rights, together with the appropriate to sexuality itself.